What is autism?

Understand autism, strengths and challenges, and practical adjustments

Autism is a lifelong neurodevelopmental difference. It shapes how a person experiences their environment and, as a result, how they communicate, work, and connect with others.

This document introduces what autism is, who is diagnosed, and what helps in real workplaces. The focus is practical: reducing barriers and creating conditions where autistic people can thrive.

In te reo Māori, the Indigenous language of Aotearoa New Zealand, one word used for autism is Takiwātanga, meaning “in their own space and time.” It is a reminder that autistic people may experience the world differently, not wrongly.

Autism affects people in different ways. Some autistic people mask, meaning they hide their differences to fit in. Some do not. Autism can also overlap with intellectual or learning disabilities, and epilepsy. These overlaps can affect access to education, work, and support.

Research points to several differences that are commonly associated with autism, including:

- Sensory processing differences

- Differences in communication between brain regions

- Stronger anxiety pathways linked to fight, flight, or freeze

- Slower processing speed in some tasks

- Strong memory skills, including difficulty filtering out irrelevant information

Many autistic people experience sensory input more intensely. Too much light, noise, or changes in temperature can cause pain or anxiety. Sustained eye contact can feel intense or frightening.

Autism is commonly described through patterns that include:

- Differences in socialising and communication

- Sensory sensitivity

- Deep interest in repetition, routines, or predictability

Some autistic people do not use speech and may communicate using assistive technology, writing, or other methods. This is not a reflection of intelligence or ability. Some autistic people are hyperlexic, meaning they read and write exceptionally well and fast.

Empathy and emotions

A common myth is that autistic people do not have empathy. This is not accurate.

Empathy includes emotional empathy (feeling with someone) and cognitive empathy (imagining what another person might mean or be experiencing). Autistic people can experience empathy very strongly. Sometimes it is so intense that they shut down. From the outside, this can look like not caring, when the opposite may be true.

Some autistic people also experience alexithymia, which means difficulty recognising and naming emotions. This can make communication hard during times of high emotion, especially under stress.

Who is diagnosed

Autism occurs in around 1–2% of the population worldwide.

Historically, diagnosis rates were reported as higher in males than females. We now understand that many women learn to mask and may be diagnosed instead with anxiety or personality disorders. Diagnosis patterns are changing, and one of the fastest-growing groups receiving a diagnosis is adult women.

There are also race and cultural differences in diagnosis rates, alongside barriers for people living in poverty. These differences are more likely linked to social factors and access to professionals, not biology.

Some autistic people fit a profile known as Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA), where direct demands trigger extreme anxiety, leading to shutdown or anger responses. This is rarer, but it can be very disabling. Support that reduces anxiety and pressure can help.

Diagnosis and everyday experience

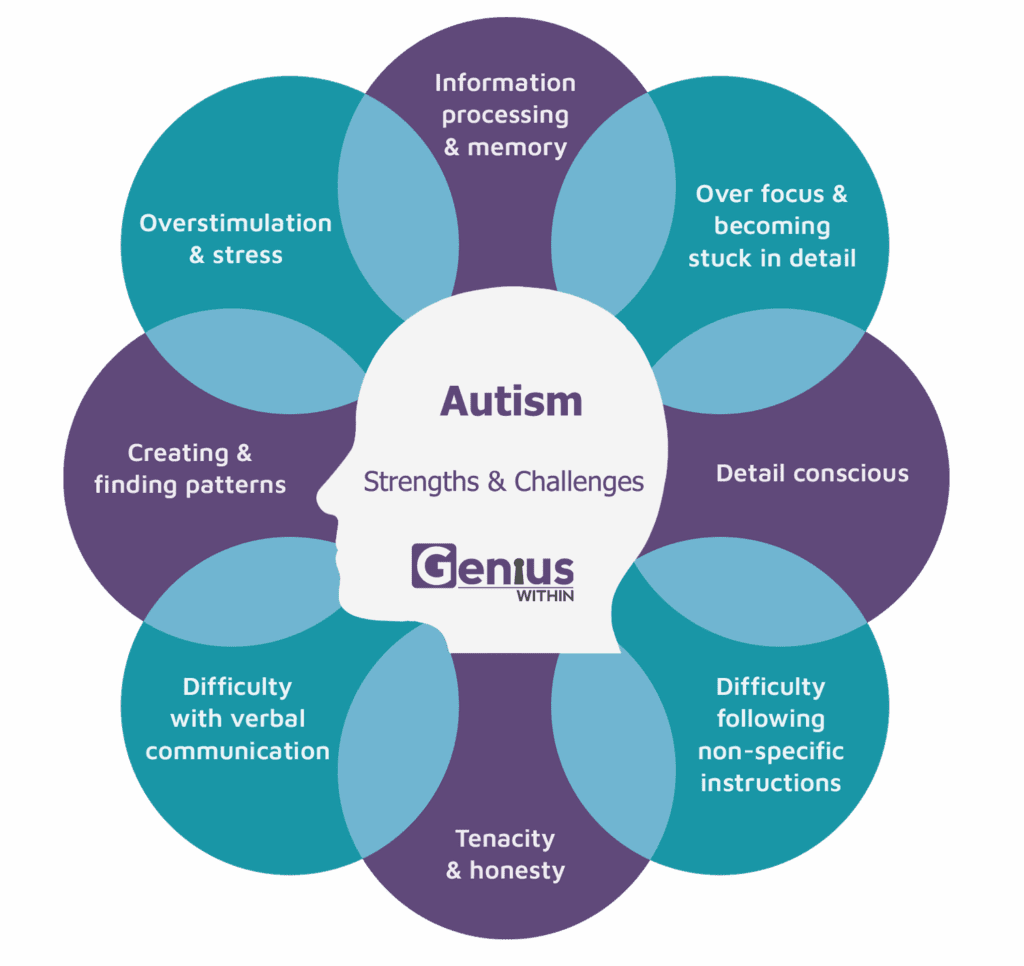

Autism is defined clinically through diagnostic criteria that focus on patterns of communication, social interaction, interests, and sensory processing. In everyday life, these same features can be understood as part of a person’s unique profile of strengths and challenges.

A diagnosis of autism typically involves:

- Differences in social communication and interaction, such as understanding social cues or interpreting tone of voice

- Repetitive behaviours, routines, or focused interests, often linked to a strong need for predictability

- Differences in sensory processing, with heightened or reduced responses to sound, light, texture, or movement

These criteria help professionals identify autism, but they do not capture the full richness of autistic experience. Many of the characteristics described here also underpin valuable skills that support problem-solving, creativity, and collaboration.

Different presentations of autism

Autism may look very different from one person to another. Some people communicate confidently and mask their difficulties. Others may communicate differently or require daily support. Neither presentation is more or less valid.

Masking, consciously or unconsciously hiding autistic traits to fit in, is common, particularly in social or professional settings. While it can help someone navigate the world, it often comes at a cost, leading to exhaustion, anxiety, and autistic burnout. Creating environments where people can be authentic reduces the need for masking and supports wellbeing.

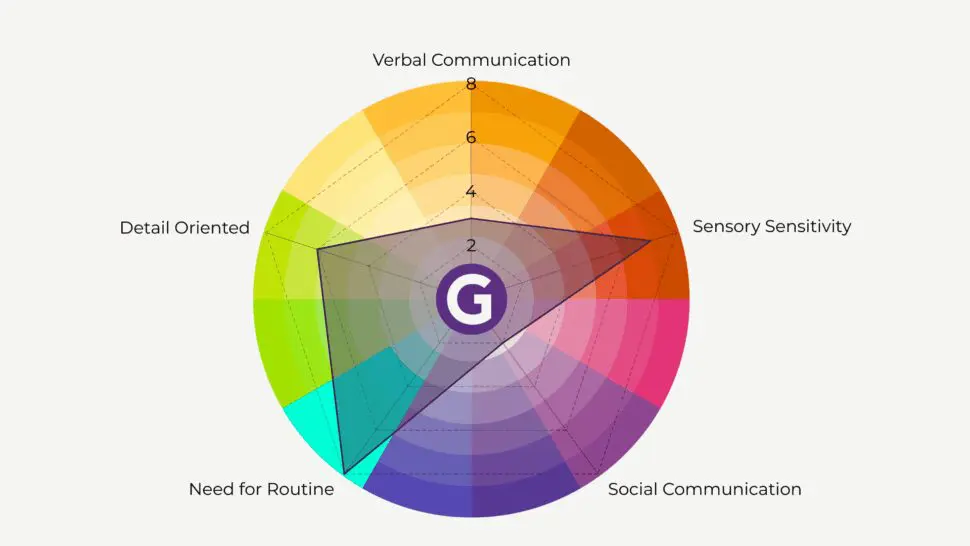

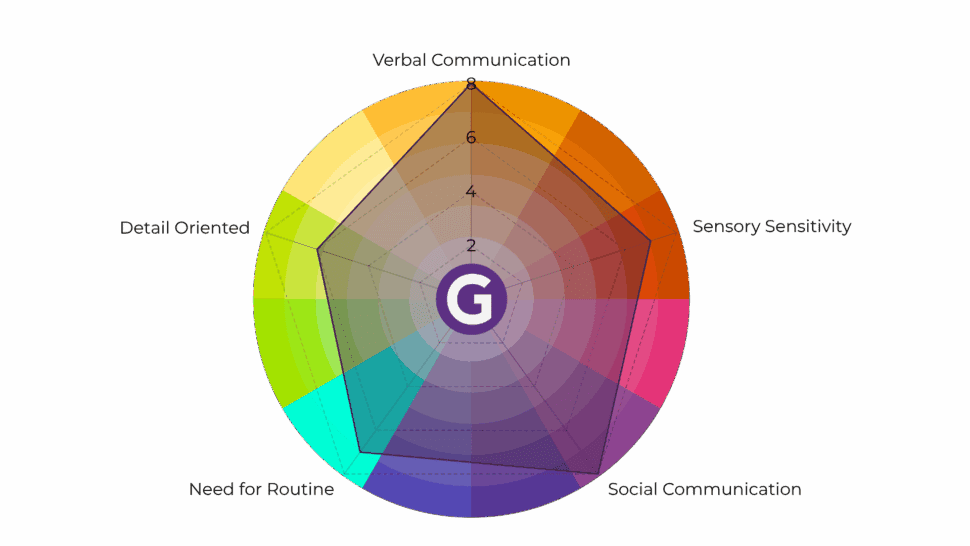

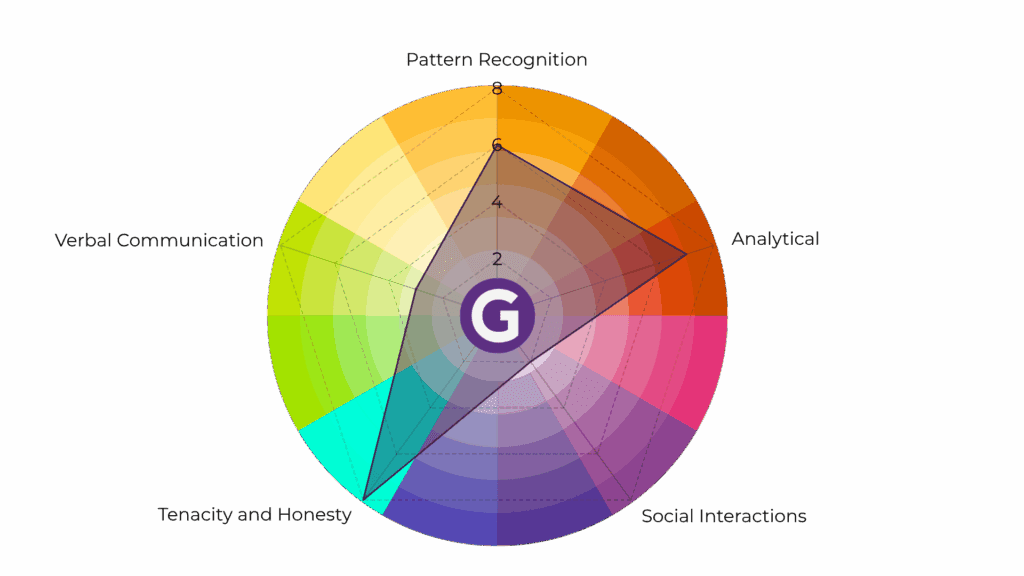

Rather than visualising autism as a line from mild to severe, it is more helpful to think of it as a colour wheel. One person may find communication difficult but have exceptional creative or analytical ability. Another may have strong verbal skills but need structure and routine. Both are equally autistic, simply expressed in different ways.

Strengths and Challenges at Work

Autistic people often bring real strengths, including:

- Deep focus and specialist expertise

- Strong long-term memory

- Pattern recognition and innovation

- High honesty, transparency, and ethics

Autistic people can also struggle with overwhelm and may shut down when things become too much. Triggers can include:

- Sensory overload (noise, light, heat, smells, busy spaces)

- Confusing or inconsistent messaging

- Too many tasks, changes, or interruptions

Miscommunication can happen even when everyone is trying. A manager may believe they gave a clear instruction, while an autistic colleague interprets it differently. The result may be extremely detailed work, but not what was intended. This can be frustrating for both sides.

Detail-based thinking can also create “freeze” moments at the start of a task, while the person works out where to begin. Deadlines and prioritising “good enough” over perfection can be difficult without clear structure.

How Genius Within approaches autism inclusion

Genius Within’s approach is grounded in the biopsychosocial model of neurodiversity at work, developed and applied through the work of Dr Nancy Doyle and colleagues. This model recognises that outcomes for autistic people are shaped not by neurology alone, but by the interaction between biological difference, psychological experience, and social and organisational context.

In practice, this means we do not locate difficulty solely within the individual. Instead, we examine how workplace systems, job design, leadership behaviours, communication norms, and sensory environments either support or undermine performance and wellbeing.

Our work consistently shows that many challenges attributed to autism are actually predictable responses to environments that demand constant adaptation, ambiguity, and sensory endurance. When clarity, predictability, and psychological safety are improved, autistic strengths are more likely to emerge and be sustained.

We also recognise that autism rarely exists in isolation. Many autistic people experience overlapping traits associated with ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia, anxiety, or trauma. Drawing on contemporary research, we use a transdiagnostic lens to identify shared patterns of need and capability across neurotypes, rather than treating diagnostic labels as silos.

This approach shapes how we design interventions. We prioritise:

- environmental and systemic change alongside individual support

- clarity over assumed social norms

- predictability over pressure

- shared responsibility for inclusion, rather than forced adaptation

Our aim is not to help autistic people conform to existing systems, but to help organisations build systems that work for a wider range of minds. This reflects a growing evidence base showing that inclusive design reduces burnout, improves retention, and supports sustainable performance.

This is not a theoretical position. It is informed by peer-reviewed research, lived experience, and years of applied practice across workplaces. It is why Genius Within focuses on changing environments as well as supporting individuals.

Shared understanding: the double empathy problem

The double empathy problem helps explain why misunderstandings can occur between autistic and non-autistic people. Autistic people are often expected to adapt to non-autistic communication norms, while autistic communication may be labelled as blunt or difficult.

A fairer approach is shared responsibility:

- Agree that eye contact is not required to show respect or attention

- Accept different communication styles, including directness

- Focus on clarity, not guesswork

What helps in practice

Simple, practical adjustments can make a significant difference for autistic people at work. These are not specialist interventions. They are everyday design choices that reduce unnecessary friction.

Common examples include:

- clear instructions and expectations

- advance notice of changes

- predictable routines and agendas

- reduced sensory overload

- flexible ways to participate in meetings

The challenge for many organisations is not whether to make adjustments, but which adjustments will help this person, in this role, in this environment.

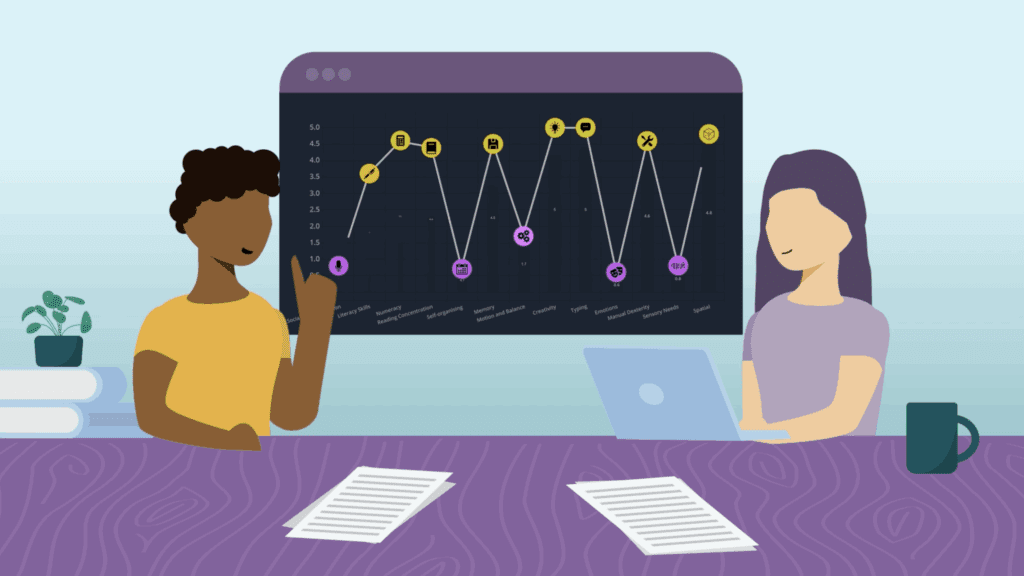

This is where a strengths- and needs-based approach is essential. Tools such as Genius Finder help individuals and organisations understand how someone works best, including their cognitive preferences, sensory needs, communication style, and support requirements. Rather than relying on assumptions linked to diagnosis, this approach focuses on practical, personalised adjustments.

When adjustments are informed by this level of insight, they are more likely to be effective, proportionate, and sustainable. Clarity improves, misunderstandings reduce, and people are better able to do their best work.

When environments are designed with neurodivergent people in mind, communication improves, burnout reduces, and performance becomes more sustainable for everyone.

Quick myth check

- Autistic people have no empathy: False

- Autistic people might communicate differently at work: True

- Autism is related to strong memory skills: True

- Autistic people should only be given repetitive work: False

Want to make your workplace more autism-inclusive?

Genius Within supports organisations to make work more accessible through practical adjustments, training, coaching, and strengths-based approaches.

Talk to us about autism-inclusive workplaces.

Further reading

Article by Dr Nancy Doyle: Neurodiversity at work: A biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults

Funding

You may be able to get funding through the Access to Work scheme. If you have funding, you can come straight to us, no matter who is recommended on the referral – it’s your choice! We are approved suppliers UK wide.